The Chinese Hukou system, all but obsolete?

Study finds Hukou registration thresholds at 12.6% nation-wide, remain tight only in 9 metropolises

Household registration, or the hukou system, has long been a hallmark of China’s social management model, to which people’s social status, access to welfare, and educational opportunities are tied.

Due to seismic demographic and economic shifts in Chinese society over the past few decades, the hukou system has been loosening its grip, according to a new study by two economists based on a quantitative analysis of reforms between 1996 and 2024.

Key finding

The study finds that the overall “hukou threshold” across 332 Chinese cities has fallen to 12.6 percent, down from 98.8 percent in 1999. In other words, on average, Chinese cities now block just over one-tenth of would-be hukou holders from obtaining local registration. This suggests that Chinese people are freer than ever to move around the country for work or other purposes, and that the ongoing erosion of hukou barriers is likely to continue in the foreseeable future.

This newsletter is based on an interview by Southern Weekly, which also made the charts in this newsletter. Original interview here.

Breakdown

The study was conducted by Zhang Jipeng, an economics professor at Shandong University, and Chen Zhu, a PhD candidate at the Southwestern University of Finance and Economics. Their paper, titled 《户籍制度改革与城市落户门槛的量化分析:1996-2024》, was published in 2024.

The authors collected hukou registration regulations from 332 Chinese cities, including centrally administered municipalities and prefecture-level municipalities, leaving out only a handful of cities that had no clear and publicly available rules on hukou registration. (Not sure what centrally administered municipalities and prefecture-level municipalities are? See this explainer by David Fishman.)

The study focuses on people aged 15 to 64 whose reason for relocating was work, starting a business, or moving as a result of the rezoning of their original place of residence.

The study measures hukou stringency using a “threshold level,” defined as the difficulty of obtaining local hukou in a given city. More specifically, the researchers calculate the ratio of people eligible for a city’s hukou to all non-hukou residents in that city, and then subtract that ratio from 100 percent.

For example, if City A has 1 million non-hukou residents and 600,000 of them are eligible for local hukou, then the hukou threshold for the city is 100% − 600,000/1,000,000 = 40%.

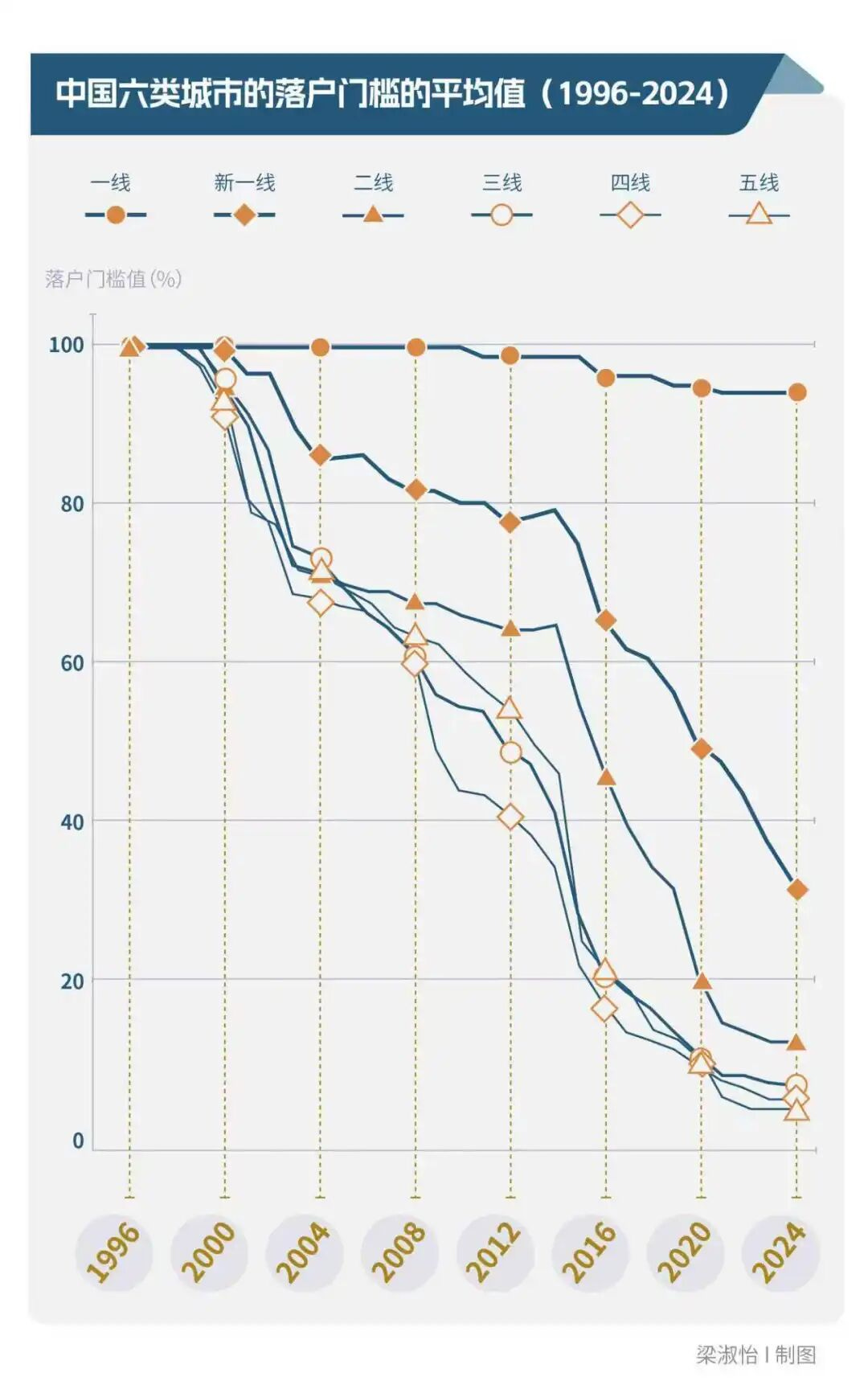

The study categorizes Chinese cities into six tiers and finds that the lower the city tier, the lower its hukou threshold and the faster that threshold has fallen.

At present, 92.77 percent of cities have thresholds below 20 percent, and 48.9 percent of all cities have no threshold at all. Fourth- and fifth-tier cities now have essentially no thresholds. On average, fifth-tier cities have a hukou threshold of just 1.27 percent. In 17 provinces, all cities have thresholds below 20 percent.

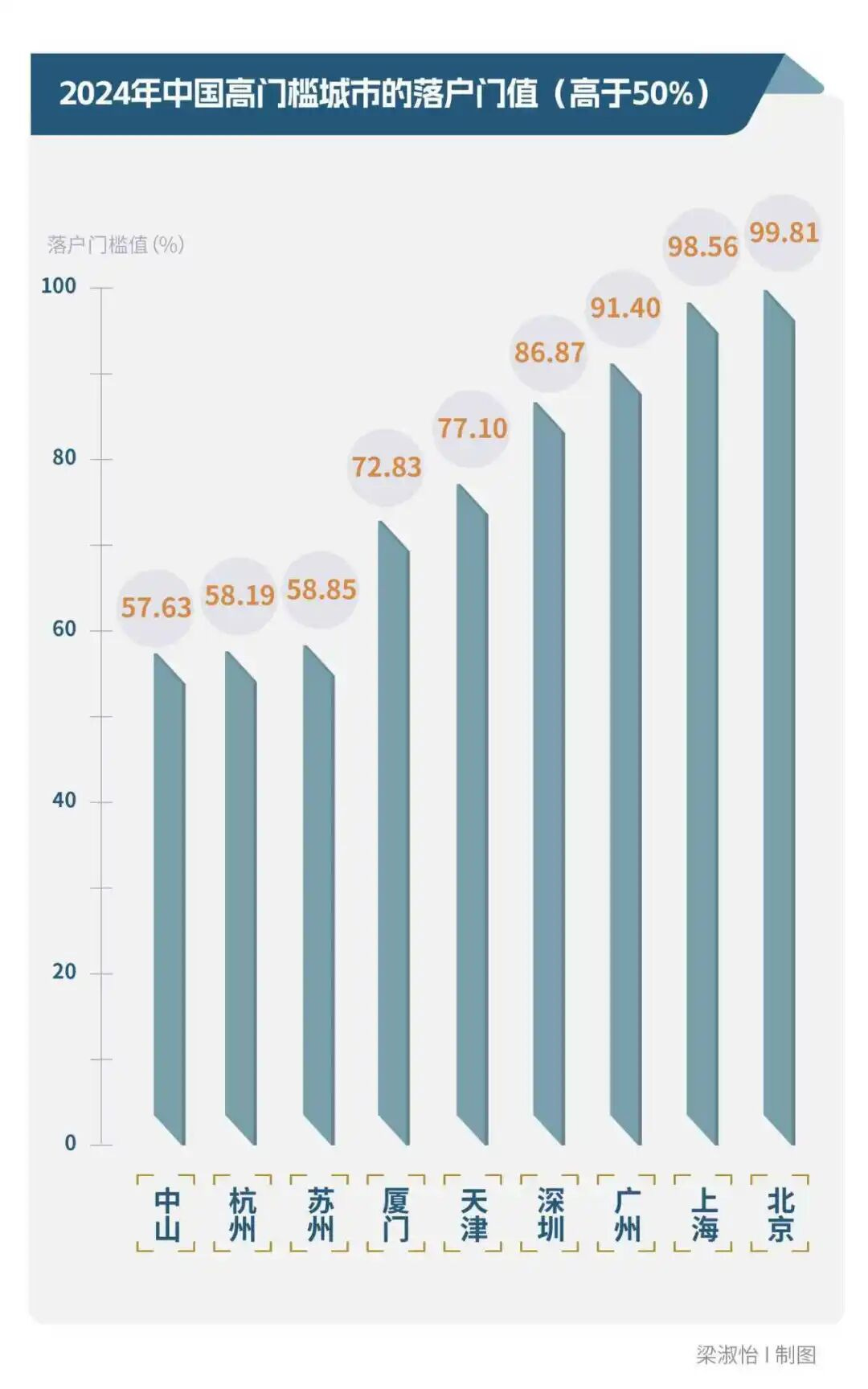

Only nine cities still have a hukou threshold above 50 percent. They are the centrally administered municipalities of Beijing, Shanghai, and Tianjin, as well as the economically developed cities of Guangzhou, Shenzhen, Xiamen, Suzhou, Hangzhou, and Zhongshan.

The study finds that the key driver of the decline in thresholds is top-down policy. Thresholds fell rapidly after two central-level policy initiatives in 2001 and 2014, especially after 2014.

Note: here, yours truly will just add a bit of context for Hukou reforms in China. China adopted a rigid Hukou system before 1978, creating a huge barrier between urban and rural populations. Since market reforms began in 1978, hukou regulations loosened to allow more farmers to settle in cities to satisfy the demand for labor there. Entering the 2010s, Hukou reform started to be considered a tool to promote fairness in society and the balance of development, as it gave people more freedom to relocate to cities that provided better public goods. This mindset is consistently embodied in major top-level policy papers, including the Proposal for the 15th Five-Year Plan that was released in October.

From 1999 to 2003, average hukou thresholds fell from 98.8 percent to 69 percent, then to 30.5 percent in 2016, and further to 12.6 percent in 2024. As the chart above indicates, however, different cities have reduced their thresholds at very different speeds.

Beyond top-level directives, cities themselves also have strong incentives to lower thresholds. Several types of cities are especially eager to relax their rules:

· Cities with more vibrant manufacturing sectors and stronger demand for labor

· Cities with more severe population aging

· Cities facing more intense competition from neighboring cities

· Cities with sluggish real-estate markets

· Cities located close to top-tier metropolises

What happens next, especially in major cities?

Zhang expects thresholds to keep falling, albeit at a slower pace, and to move down in small steps rather than through one sweeping reform. Possible measures include expanding hukou quota programs, lowering eligibility criteria, or first allowing hukou registration in suburban areas.

Does all of this mean the hukou system is becoming irrelevant?

Yes and no, according to the study.

Yes, it is now much easier to obtain hukou in the vast majority of cities. But no, because many government-provided services are still tied to hukou status. In other words, while it is no longer very difficult to change your hukou, it remains a necessary step to access many public goods.

Don't those giving up registration in their old locality give up property rights when they move registration?

I do not know if those rights are valuable but I am baffled as to why this issue has not been resolved.

Also wonder if hurdles to moving registration are such that many simply do not apply as they would be denied. In other words, the study might not mean anything at all. Not saying I know this is the case, but I know I've seen plenty of similar studies in areas I was familiar with and I found them laughably off-base.

Hukou barriers persist exactly where coordination density is highest.

That suggests the system isn’t obsolete, it’s concentrating around the few cities that still matter institutionally.